10 July 2020, Apia, Samoa – As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on across the globe, the linkages between ecosystem degradation and the loss of biodiversity, and the emergence of infectious diseases, was discussed during the final session in the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme’s (SPREP) webinar series “Transitioning to a post-pandemic Pacific”.

As humans, we depend on biodiversity and healthy ecosystems for our health and survival. Biodiversity, and the complexity of our landscapes and seascapes, is integral to social and ecological resilience, including the provision of ecosystem functions and the services that they sustain.

As genetic and species diversity is lost and ecosystems are degraded, the complexity of the overall system is compromised making it more vulnerable, and potentially creating new opportunities for disease emergence and poor health outcomes in both humans and species.

The webinar, titled “One Health: Healthy Environment = Healthy Humans”, explored the risk posed to our Pacific ecosystems and species, and what that could mean for our Pacific people’s health and wellbeing.

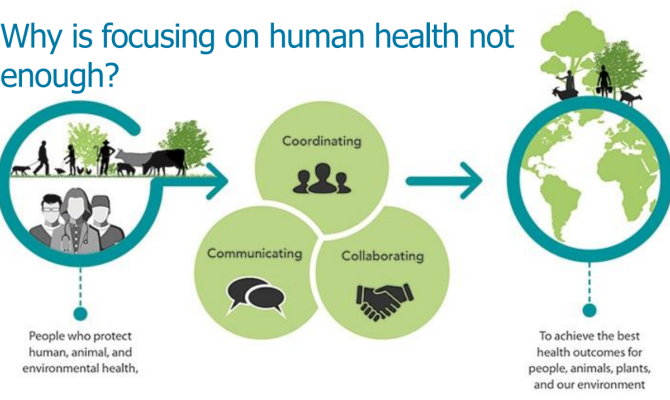

It also examined a new concept known as “One Health” which is a strategy for pooling our knowledge and data collection across multiple sectors managing health and the environment to ensure an integrated approach to better environmental management, leading to better health outcomes and reduced risk of diseases.

The panel of speakers included Dr Stacy Jupiter, Director of the Melanesia Program with the Wildlife Conservation Society; Dr James Russell, Conservation Biologist with the School of Biological Sciences of the University of Auckland; Dr Nasir Hassan, Climate Change and Environmental Health Team Coordinator at the World Health Organization (WHO) South Pacific office; and Dr Collin Tukuitonga, Associate Dean of the Pacific Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences of the University of Auckland; and Dr Angela Merianos, Pacific Health Security, Communicable Diseases and Climate Change of the WHO South Pacific Office.

Dr Jupiter revealed that the majority of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, with 72% of emerging zoonoses outbreaks originating in wildlife, with the rest from domestic animals, and the frequency is increasing.

“Connected human society greatly increases long-distance transport of disease vectors, with the increasing number of human-wildlife interfaces such as markets. Connectivity also facilitates subsequent human to human transmission.”

Dr Jupiter also pointed out that ecological degradation increases the overall risk of emerging infectious diseases. In the Asia-Pacific region, the number of zoonotic disease outbreaks is positively related to the number of threatened mammal and bird species. More zoonotic diseases have been found in threatened species facing decline in habitat or high pressure from over-exploitation.

Speaking from Auckland, New Zealand, Dr James Russell, said that the loss of biodiversity and the outbreaks of infectious diseases have been driven by species that have been introduced, or invasive species such as rats and mosquitoes.

“That’s why biosecurity is so important. We already know this from managing invasive species; we know we have to do things pre-border and post-border, we have to prepare for when things depart from their origin, we have to manage a quarantine process, and manage invasive species on vessels. When they do arrive at our borders we have to be prepared to deal with them,” Dr Russell said.

“It’s important to bear in mind that the probability of preventing diseases and species establishing decreases the further along the biosecurity pathway and prevention processes,” he added.

Dr Russell used the case of New Zealand, which successfully eliminated COVID-19 using a similar process, and that New Zealand learned from what they already knew about invasive species – not to look at it as something that will never arrive because they will inevitably arrive, and to be prepared and know what to do for when that happens.

Dr Collin Tukuitonga, Associate Dean of the Pacific School of Medical and Health Sciences of the University of Auckland, and also the former Director General of the Pacific commended the response by the Pacific islands, many of which have managed to remain COVID-19 free thanks to swift responses from their governments. In the case of Samoa, he said that the measles epidemic, which claimed more than 80 lives at the end of 2019, no doubt had a big influence in the way people think and the way the government was quick to act with the threat of COVID-19.

He was quick to note that although the Pacific and the world is facing the threat of COVID-19, other existing threats still remain for Pacific islanders, such as non-communicable diseases, and the single greatest threat to the security and livelihoods of Pacific islanders, which is climate change.

This was echoed by Dr Nassir Hassan, who said, “It is very clear that COVID-19, whether we like it or not, is a reminder of the intimate and delicate relationship between people and planet. Any efforts to make our world safer are doomed to fail unless they address the critical interface between people and pathogens, and the existential threat of climate change, that is making our Earth less habitable.”

Dr Angela Meranos of the World Health Organization’s South Pacific Office elaborated more on why “One Health” is important for the Pacific.

“In the Pacific, a number of diseases like brucellosis, leptospirosis, seafood intoxications like ciguatera and vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever are all examples of diseases or toxins that originate in animal hosts and vectors and can ultimately cause human illness.”

“Locally acquired zoonotic diseases may be of low incidence in the Pacific island countries but establishing intersectoral relationships before the next big event is crucial to achieving a well-coordinated response.,” Dr Merianos added.

“Cross-sectoral surveillance, monitoring and data-sharing across fields of ecology, human and animal health are all important contributors because we know that there are, in certain situations, communities that are unable to apply the type of biosecurity measures that we would regard as optimal to stop spill-over events and emerging infectious diseases.”

The webinar was hosted by SPREP’s Island and Ocean Ecosystems Programme, and was the culmination of a 5 week series which aimed to drive Pacific conversation which empower a “blue and green” component in the COVID-19 recovery plans for Pacific island countries.

The full webinar is available on YouTube at this link.

For more information on this webinar, please contact Ms Amanda Wheatley, Biodiversity Adviser, at [email protected], or Ms Juney Ward, Biodiversity and Ecosystems Officer, at [email protected].